| Posted in:Copyright

Cariou v. Prince

A recent case that is bound to have a significant impact in both the art and legal worlds is the Second Circuit’s decision in Cariou v. Prince, 714 F.3d 694 (2d Cir. 2013). In 2000, French photographer Patrick Cariou published a book length photography collection entitled Yes, Rasta, depicting members of Jamaica’s Rastafarian community. American artist Richard Prince, a practioner of what has come to be called “appropriation art” used 30 of Cariou’s Rasta photos in his own series called Canal Zone. Prince’s “rephotographs” generally involved taking Cariou’s photos and resizing them, blurring or focusing them, or combining them with various other works. Cariou sued for copyright infringement and won in District Court, with Judge Deborah Batts finding that Prince’s appropriation did not qualify as transformative because it did not offer any sort of commentary of the original photographs. Prince had argued that the appropriation of the original images for use as “raw material” in a new context was per se fair use and admitted that he did not intend to comment or transform Cariou’s images. Batts was unconvinced by Prince’s copyright maximalist point of view.

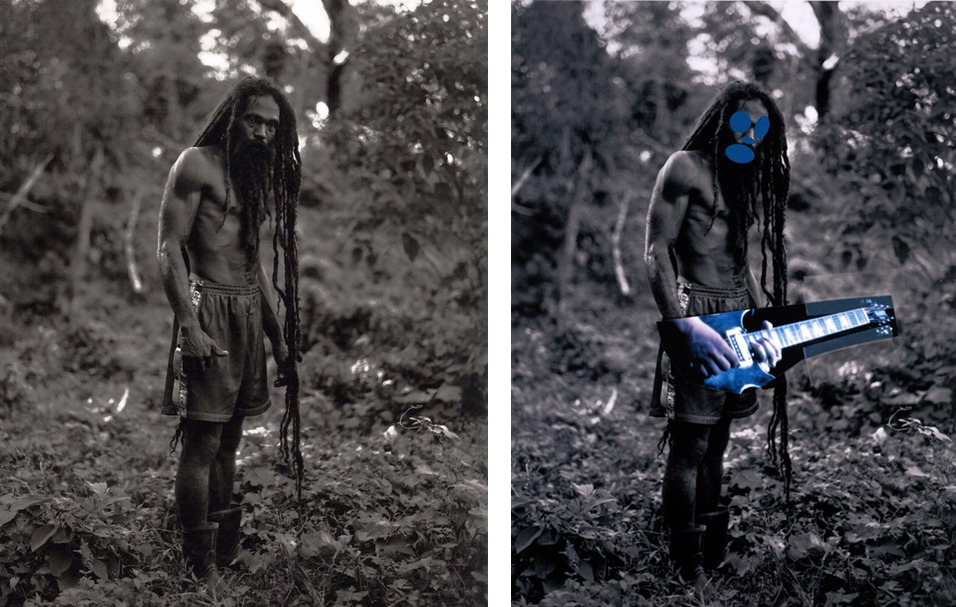

LEFT photo from Patrick Cariou’s original collection of photographs vs RIGHT photo from Richard Prince’s work titled “Graduation”

Fair Use Considerations

Under 17 U.S.C § 107, a fair use of copyrighted material for purposes such as criticism, teaching, comment, or research can be a complete defense to a charge of copyright infringement. In making a determination as to whether the fair use defense applies, the statute provides four factors for courts to consider:

- The purpose and character of the use (i.e. whether it has been taken to use in a commercial context and how it has been used in the new work);

- The nature of the copyrighted use (whether it is expressive or creative or factual or informational);

- The amount of the copyrighted work taken in proportion to the whole; and

- The effect of the new use on the market for the original work. Fair use exists as a defense to protect those who take from a copyrighted work for a valuable purpose that does not significantly damage the original copyright holder, or whose value is sufficient to accept some limited damage to the copyright holder.

Transformative

The key word in Cariou v. Prince, as it is in so many fair use cases, is “transformative.” The concept of transformativeness primarily relates to the first of the four fair use factors, and according to the Supreme Court, “[t]he more transformative the new work, the less will be the significance of other factors, like commercialism, that may weigh against a finding of fair use.” Since the Court laid down this pronouncement, the idea of transformativeness has gone through its own transformation. Since the Supreme Court’s 1994 decision in Campbell v. Acuff-Rose Music, 510 U.S. 569, a major focus of any fair use analysis was whether or not the secondary work commented in some satirical, parodic, or critical manner on the original work. In Campbell, Hip-Hop group 2 Live Crew used the tune of Roy Orbison’s famed rock ballad “Oh, Pretty Woman” for its parody song “Pretty Woman.” The Court eventually found that the parody was protected under §107 and a major part of this determination had to do with the relationship between the two works. According to Justice Souter, “[f]or the purposes of copyright law, the nub of the definitions, and the heart of any parodist’s claim to quote from existing material, is the use of some elements of a prior author’s composition to create a new one that, at least in part, comments on that author’s works.” Certainly to qualify as a parody one must comment on or refer back to the original work or to the substance of the original in order to make the point. However, what if the transformative use is not a parody and does not comment on the original?

Prince’s fair use defense found far more receptive ears in the Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit, which reversed the District Court as to 25 of the 30 appropriated photos and remanded the others including “Graduation” pictured above back to the District Court for reconsideration. According to the Circuit Court, Judge Batts erred in specifically requiring the allegedly infringing work to refer back to, or to comment upon, the original copyrighted work as a prerequisite for fair use protection.

According to the Second Circuit, Prince’s work, though admittedly not intended as comment or critique had “transformed those photographs into something new and different.” To some this would appear to be as much an aesthetic judgment as it is a legal one. Nevertheless if the original is transformed in the creation and brings about new insights or understanding, this is what the law favors and will apparently protect.

While many in the contemporary art community applauded the Second Circuit’s ruling (including the Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts and the Robert Rauschenberg Foundation, which each filed briefs on Prince’s behalf claiming that artistic fair use cases require an art history context that most judges will be unable to bring to a case) many copyright holders and their attorneys have been left with a feeling that the copyright owner’s right to control the use of his or her copyrighted expression by creating derivative works has been compromised.

A derivative work is one which is substantially based on a prior, original work. The line where a derivative work ends and a transformative one begins is not altogether clear. This will take the trained eye of an experienced practitioner to discern.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Larry Mandel, Esq. provided the review of the Cariou v. Prince case because this is an area that comes up frequently in his copyright practice and this case is a dramatic example of how the case law evolves and of the importance of keeping up with changes in the law.

IP Lawyer Blog

Intellectual Property Law blog posts from www.iplaw-gmp.net. Call 732-363-3333 for an attorney in Patents, Trademarks, Copyrights, & Unfair Competition. Serving NJ, NY, PA for legal, technical & business issues.